15. Developing product principles

How to build consistency into your product decisions

Welcome back! I’m Vincent and this is a Product Manager’s Notebook, a series of notes for people who are interested in sharing and learning the art of product management and career development. You can read my archive here.

If you appreciate reading this post, please consider liking and subscribing.

It’s been a while

First off, an acknowledgement that the frequency of these posts has changed drastically in the last month. My return to work from parental leave meant a colossal amount of work awaiting for my return. This, as well as life with two small children makes you choose what to prioritise.

I will say that I was surprised by the amount that was waiting for me when I came back. Decisions were left pending, conversations left on the back burner…and all of this of course causes downstream impact.

Why haven’t we kicked off X sales campaign? (I wasn’t there)

Why wasn’t Y prioritised for Engineering in Q1? (I wasn’t there in Q4 for planning)

Why aren’t we further along the development cycle for Z than we should be? (please see previous notes)

All this is to say that: I’m glad to be back at work, but it is a lot.

Work-life balance is hard to navigate and corporate life is not particularly understanding of the fact you had 3 hours’ sleep because you were scrubbing your child’s vomit out of the carpet the night before. Life moves on.

As we try and work out how to bring up our children, one of the things top of mind is how to instil them with the right principles. When faced with a decision, how do we help them to learn how make the right ones, to decide based on what’s right or wrong, fair or unfair? Especially when we’re not around?

A similar problem arises for product management, and the term “product principles” comes up often in literature. What does this mean?

Product principles in theory

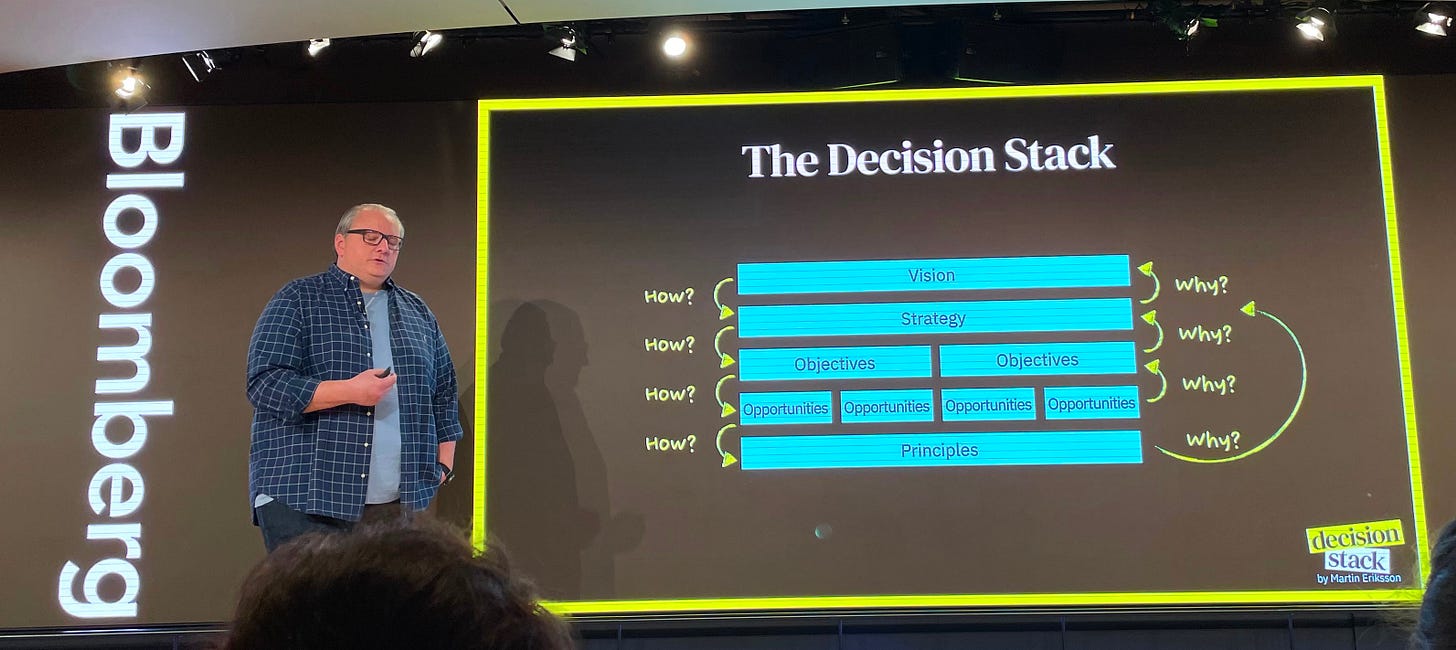

Last year we had Martin Eriksson, renowned product coach and founder of Mind the Product come into our office to give us a talk about the Decision Stack, which has become his main topic over the last few years.

Core to the idea of decision stack is the setting of product principles, which describe the principles you're willing to follow and trade offs you're willing to make to help to make decisions easy.

Another way of looking at it, the principles help you to avoid making decisions that don't create long-term value for your company/customers or are against your values.

Easier said than done.

Product principles were not a topic that had been discussed before and sometimes product people see principles as an academic exercise, to be created once on the suggestion of a product coach and then forever forgotten. Also, who has the time in the day to sit down and think, really think, about principles?

At the end of the day, if you really care about them, it makes sense to make time for them. Just like we do for our kids, establishing these principles is important to encourage consistent behaviour and decisions that can be made with or without you.

That’s how over the past year since Martin’s lecture, I have been conscious - I wouldn’t go as far as call it a mission, of defining these principles to make decision-making a less onerous task.

What I have found is that the principles often already exist to some degree with our product leaders. However, they can be very subjective and challenging to tease out, and only comes out when we assess different decisions. However, the point of product principles is to make trade-offs in your product more explicit and be more decisive.

Things I learned along the way:

We care about the managing of risks (legal, licensing, reputational) even over revenue generation

We care about allowing customer workflows, even over revenue generation

We care about building consistency across products, even over product customization

This has helped to make decisions about blocking existing functionality, introducing new features, as well as commercial decisions on our business model.

Empowering product managers to say “No, because”

Perhaps the most useful thing I’m learning from principles is to have a stronger opinion on what we won’t do and the ability to explain WHY.

No, we wouldn’t block access to premium data based on environment because we can allow customers to try data and use controls to restrict or limit.

No, we don’t want to push users to Enterprise products with limitations on the free model, because the focus should be on building benefits to Enterprise customers

No, we shouldn’t build a product feature in a particular way because of concerns about security and access management that would be inconsistent with other ways we handle these risks in our product

No, we shouldn’t have different commercial rules of the same datasets in different platforms because we want a consistent experience for customers across our product lines

Sometimes, the decision seems obvious when it’s been made explicit. However, without product principles in place, it is easy to take the opposite stance. Often times both cases can be argued. Customisability could be seen as being more important than consistency, though you will notably then introduce new product-specific logic on the back end that will need to be maintained - arguably those are implementation concerns.

It’s about trade-offs at the end of the day.

Taking the next step

So principles are clearly a useful tool in the product manager’s arsenal, and it’s no wonder that many like to claim to have “principles-first” thinking.

How do you go about establishing what these are?

1. Review previous product decisions

Take a look at previous decisions you and your team have discussed and made. What has been consistent and what has stood out? What made you go “oh of course we decided that in that way” and what were difficult decisions that were made after many rounds of discussions?

That’s a good way to start identifying existing principles you already have.

2. Start talking about it

As awkward as it is to be the one to kick it off, bring your findings to discussions with your team or management layer - if they’re open to it.

There’s nuance needed here, since no-one is going to appreciate it if you call out inconsistency in your product decisions. The point is that being explicit about your principles helps us all to make our work easier in the future, since it gives us clear reference points that don’t rely solely on our individual experiences.

3. Document and continuously iterate

Now that you’ve identified and agreed what principles drive your decisions, write them down with examples that demonstrate what they mean. Mine are available on an internal documentation page that is accessible to all - somehow writing them out makes them more real.

Make them known and continuously review these as time go by to make sure they’re still relevant and we still agree with them. Product principles are not meant to be a “one and done” exercise. Assumptions change. Markets change. Strategic priorities move on. Your principles will too.

This is all to say that establishing product principles for your product is worth the effort, not only in helping you to build confidence in making strategic and tactical decisions, but also giving others a sense you know what you’re doing as the leader for your product. As you grow, you want to start learning the principles beyond your product - those for your product group, your business lines and your company.

These will help you to influence bigger decisions and directions to take as you develop on the next evolution of your product - and your career. Best of luck! 🫡

Welcome back, Vincent!